Jennifer Callaghan

Jennifer came to Wisconsin later in life, but has fully embraced the great state of Wisconsin as home. Her first career was as a professional ballet dancer, but a lifelong passion for nature and animals led her to a second career in environmental biology. She loves to learn new things and share her love of nature with others. In her free time she likes to travel and stay active with her awesome husband and sweet little dogs.

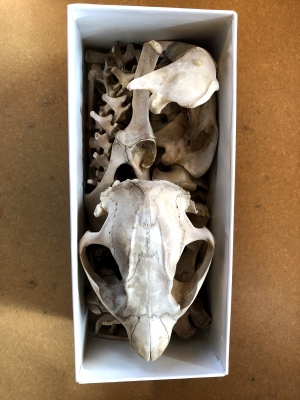

A gift of an American Beaver skeleton

Late last February, we received an email from a community member about a beaver found dead in Riverside Park. This news was especially disheartening to us considering the near celebrity status the Milwaukee River Greenway beaver couple had gained not only publicly, but amongst staff. We had watched the activities of the beavers in Riverside Park for nearly five years and enjoyed hearing the stories from other staff and community members about their encounters.

Secret Lives

As I look longingly over the Menomonee Valley river basin currently radiating with spring promise, I am reminded of last week’s bitter rain and our dashed hopes of seeing the season's first Red-winged Blackbird. But spring’s sweet whispers delivered on the high note of a cardinal’s song today again brought hope that spring was still on its way.

But, what if we weren’t driven by hope but by some kind of undeniable intuition or reverberating internal awareness? How does a wild animal adapt during an unpredictable Wisconsin winter?

Creepy Creature: Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura)

On an early morning bird walk last year, we smelled our find before we saw her. The smell of necrosis mixed with day-old vomit lingered on the light breeze. We scoured the nearby terrain trying to find the mysterious decaying matter hidden amongst the leaf litter only to remain perplexed. And then we saw her. Perched on a tree branch, just 10 feet from our heads, sat the pungent perpetrator.

A New Inhabitant In Riverside Park

Occasionally the Research and Community Science team has a find so cool that we can’t stop ourselves from sharing it. Back in 2006 I started a mammal monitoring project at Riverside Park to document the park’s population, and recently we recorded the most glorious find I have ever experienced at the UEC!

Red Wings and Early Spring

For those of you who may not know, we have an organization-wide phenology competition every year to document the first of year (FoY) Red-winged Blackbird, Eastern Chipmunk, Mourning Cloak, and Butler's Gartersnake. The documentation of these four species typically signifies the arrival of spring and the dismissal of winter. This year's unseasonal warm weather, however, has a resulted in an uncomfortably early kickoff.

Native Animal of the Month: Elk

Few things illustrate a more beautiful image of winter in Wisconsin than a cervid in the snow. The hooved creatures conjure some type of nostalgia in our minds: a docile doe grazing for food beneath powdery snow, a statuesque bull moose wading through an icy pond, or a heavily antlered elk standing in silhouette as its warm breath escapes in wispy trails. Surely you can’t refute the holiday spirit swirling through your mind when you envision such a scene?

Native Animal of the Month: Eastern American Toad

Many folk tales, urban legends, and myths have led people to believe just plain inaccurate things about some of our wild creatures. Dragonflies were believed to be the Devil’s helpers by sewing naughty children’s eyes shut while they slept. Bats were believed to get tangled in people’s hair in the dark because of misconceived poor eyesight. And, ravens were thought to be premonitions of death. I’ve heard countless critter myths throughout the years, but one creature in particular continues to surprise me with its maligned status: cue the American Toad.

Native Animal: Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis)

A potent odor in Three Bridges Park recently led us to a dead skunk lying next to the Menomonee River. It rested, amazingly intact, on a sewerage outflow pipe lightly covered in snow. Whether he was the victim of hypothermia, winter starvation or a ravenous hawk remained a mystery, but whatever the skunk’s demise, it was clear that two weeks after he had perished, his scent still lingered.

Native Animal of the Month: Eastern Screech Owl

Last fall at Riverside Park, the research and community science department was hosting the Wisconsin DNR’s bat biologists for an evening of bat mist netting, when a gregarious little screech owl paid us a visit. As DNR biologist Paul White held the large group of participants enraptured with a live bat, a persistent whinny in the distance distracted those of us at the back of the group.

Native Animal: Opossum (Didelphis virginiana)

When I think of the opossum, I think of a scrappy little character; tough, resilient, clever, and tenacious. In fact, one of my first memories of the opossum demonstrates its impressive adaptability. When tree hollows and brush piles provided inadequate shelter, the resourceful opossum sought shelter elsewhere - she would sneak in under our house's raised foundation and hunker down next to the hot water pipes beneath the bathrooms. There, she would build a comfortable bed of dry grass and stay till spring. And sometimes, when my family would take a shower or bath, you could even hear the scratching of little opossum paws against the water pipes, presumably acknowledging the relief provided by the warm plumbing.

Copyright © 2023 The Urban Ecology Center