The beaver (Castor canadensis) is a medium-sized mammal in the family Castoridae and is native to Wisconsin. The family consists of just two species – the North American beaver and the Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber). Beavers are the world’s second largest rodent, beaten in size only by the South American Capybara. Canadensis measures 35-47 inches from head to tail and weighs between 26-60 pounds. The muskrat (at right) is sometimes confused with the beaver, but the overall large size and horizontally flattened tail of the beaver easily differentiate the two.

The beaver is a semi-aquatic species that has many adaptations for life in the water. Beavers have a thick pelage with an under-layer and outer-layer of fur. They coat their outer-layer in an oily secretion which prevents water from reaching its insulating under-layer. Beavers have webbed hindfeet (picture at top) to assist in swimming and use their thick tail as a rudder. When slapped against the water, the beaver conveys different signals. They eat vegetation underwater by closing their valvular-like nostrils and sealing their lips behind the long, ever-growing incisors. Valvular-like ears help the beaver to fully submerge itself in water for periods of time. Beavers can even see underwater thanks to nictitating membranes. The membrane is a transparent eyelid which keeps the eye moist and allows the beaver to still see when submerged.

The beaver is a semi-aquatic species that has many adaptations for life in the water. Beavers have a thick pelage with an under-layer and outer-layer of fur. They coat their outer-layer in an oily secretion which prevents water from reaching its insulating under-layer. Beavers have webbed hindfeet (picture at top) to assist in swimming and use their thick tail as a rudder. When slapped against the water, the beaver conveys different signals. They eat vegetation underwater by closing their valvular-like nostrils and sealing their lips behind the long, ever-growing incisors. Valvular-like ears help the beaver to fully submerge itself in water for periods of time. Beavers can even see underwater thanks to nictitating membranes. The membrane is a transparent eyelid which keeps the eye moist and allows the beaver to still see when submerged.

Beavers live in slow-moving ponds, rivers and streams often surrounded by young forests. They are diurnal herbivores and prefer to eat the bark and leaves from willows, cottonwoods, aspens, and alders. They eat only the outermost part of trees and branches. They will often cache trees and branches in the fall in an underwater location deep enough to not freeze. This food must last them throughout the winter, so large quantities are collected at a time. In the summer, beavers supplement their diets with roots and runners from aquatic plants. Once a beaver has cleared an area of food, it will move locations to an area with a more plentiful food supply.

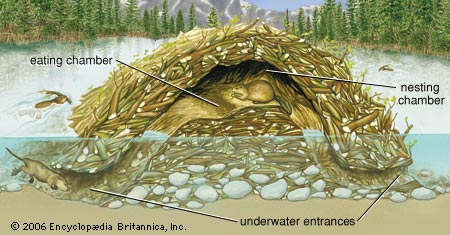

The large, ornately-constructed familial beaver lodge (at left) and dam is well-known to many, but, surprisingly beavers can also live a solo life in dens dug into the sides of riverbanks. In deep, fast-moving rivers, dams are not necessary because the water levels stay more consistent. Like a traditional lodge, bank dens may have several tunnels leading to and away from the den. They are sometimes covered in mud and twigs, but can also be an inconspicuous hole along a river’s edge. Given that a conspicuous lodge and/or dam has never been spotted in Riverside Park, chances are he is living in a bank den, eating a stockpile of roots in a well-hidden location somewhere.

The large, ornately-constructed familial beaver lodge (at left) and dam is well-known to many, but, surprisingly beavers can also live a solo life in dens dug into the sides of riverbanks. In deep, fast-moving rivers, dams are not necessary because the water levels stay more consistent. Like a traditional lodge, bank dens may have several tunnels leading to and away from the den. They are sometimes covered in mud and twigs, but can also be an inconspicuous hole along a river’s edge. Given that a conspicuous lodge and/or dam has never been spotted in Riverside Park, chances are he is living in a bank den, eating a stockpile of roots in a well-hidden location somewhere.

Beavers mate underwater in the winter and babies are born in the late-spring in grass-lined chambers or burrows. 2-5 kits (at right) are born fully furred with eyes open. They are weaned by 3 months of age, yet will stay with their mother until they reach sexual maturity. Beaver adults are rarely preyed upon, however predators of young include wolves, coyotes, foxes and bears. A beaver typically lives to 10 years of age in the wild, but a 21 year old beaver was once documented in the wild.

Beavers mate underwater in the winter and babies are born in the late-spring in grass-lined chambers or burrows. 2-5 kits (at right) are born fully furred with eyes open. They are weaned by 3 months of age, yet will stay with their mother until they reach sexual maturity. Beaver adults are rarely preyed upon, however predators of young include wolves, coyotes, foxes and bears. A beaver typically lives to 10 years of age in the wild, but a 21 year old beaver was once documented in the wild.

Importantly, beavers are keystone species! Beavers clear vegetation and provide new habitat for other critters. Birds, invertebrates, small mammals and fish benefit from new feeding and nesting grounds. And, while the results of beaver activity may look unsightly to humans, their destruction can actually be pretty beneficial. At least the mallards and white-footed mice of Riverside Park aren’t complaining. Which is why we’re not evicting our new neighbor anytime soon. Ecologically, he’s done some pretty cool things and besides that, he’s exceptionally fun to follow!

Fun Facts:

- A tightrope walking beaver!? The beaver’s tail serves an additional purpose. Besides assisting with navigation and communication, a beaver’s tail acts as a “fifth leg” by helping to balance the tree-chewing beaver when standing on two legs.

No matter who you are, construction work is dangerous! Accidents happen even when you’re a beaver. An adult beaver may lose its life by misjudging the direction of a large falling tree.

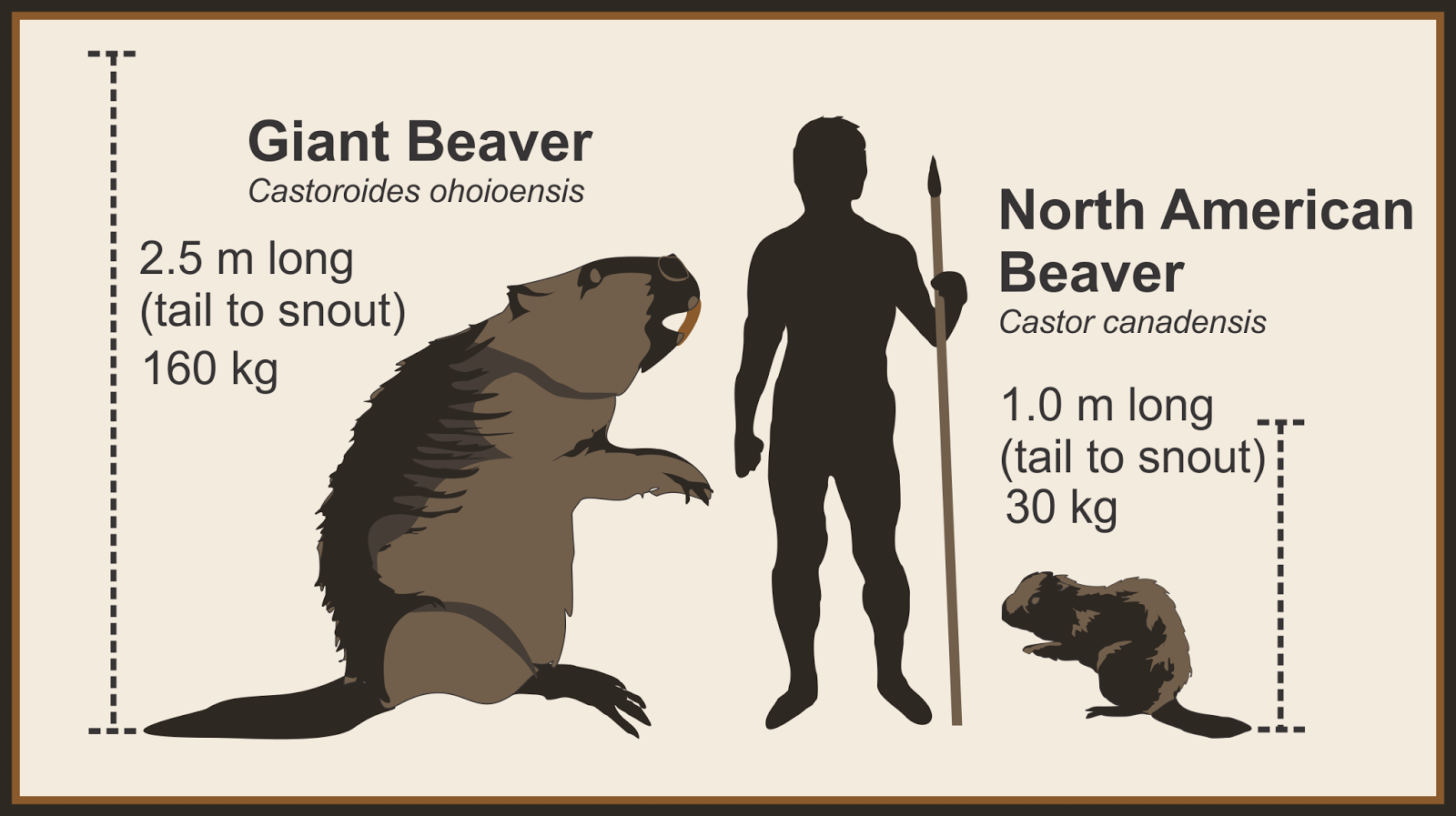

No matter who you are, construction work is dangerous! Accidents happen even when you’re a beaver. An adult beaver may lose its life by misjudging the direction of a large falling tree.- Saber-toothed Cats, Ground Sloths, Mastadons and Giants Beavers! Today’s beavers are descended from the large bear-sized beavers of the Pleistocene Epoch. They were found in fossil records dating back some 1.5 million years ago and lived as recently as 12,000 years ago. Giant Beavers weighed up to 500 lbs and had incisors 6 inches long! In 2013, a giant beaver fossil was discovered in Chicago’s Wicker Park. Just imagine Giant Beavers roaming the streets of Chicago;)

- A beaver dam from space?! The world's largest beaver dam is found in Canada and is over 2,800 ft across. Several generations of beavers have worked on this dam dating back to 1907. Click here to see photos and read more about it.

* This article was written using information from Allen Kurta's Mammals of the Great Lakes Region, Stan Tekiela's Mammals of Wisconsin, and the Illinois State Museum and Alaska Department of Fish and Game's websites www.Museum.State.il.us & www.adfg.alaska.gov

* Adult beaver and adult muskrat photos from Wikipedia. Beaver kit picture from zooborns.com website. Giant beaver comparison illustration by Todd Kristensen.