The Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentine), as the name implies, is a feisty, common turtle, found throughout the state. T his turtle’s range runs from southern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. They are incredibly tolerant of a variety of water conditions and are often the only turtle species capable of living in polluted lakes, ponds or streams, living in waters deep enough for the body to rest submerged with their head just above the water. Snapping turtles prefer slow-moving water which is more suitable to their generally sedimentary lifestyle. Water-filled ditches and sewer systems have even been known to provide adequate snapper habitat.

his turtle’s range runs from southern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. They are incredibly tolerant of a variety of water conditions and are often the only turtle species capable of living in polluted lakes, ponds or streams, living in waters deep enough for the body to rest submerged with their head just above the water. Snapping turtles prefer slow-moving water which is more suitable to their generally sedimentary lifestyle. Water-filled ditches and sewer systems have even been known to provide adequate snapper habitat.

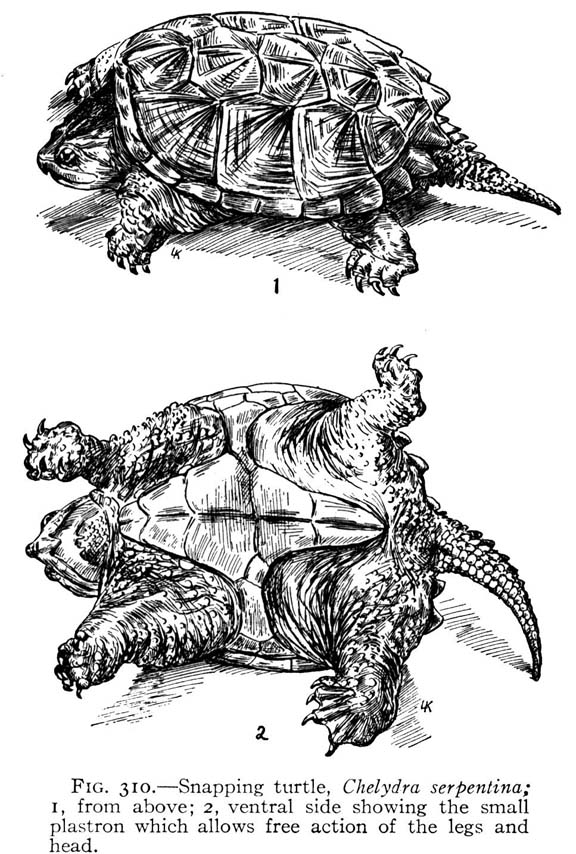

The snapping turtle is the largest and heaviest turtle in Wisconsin. A large adult can weigh up to 50 pounds and measure up to 16 inches across its saw-toothed-edged carapace. Their heads are triangular in shape with a thick neck and pointed snout. Powerful jaws and a long neck provide the turtle a commendable defense system. A reduced plastron prevents the turtle from being able to retreat into its shell, causing snappers to act more aggressively than many turtle species. However, this reduced plastron (shown above) also affords the snapper better mobility, allowing it to move easier and greater distances on land.

Snapping turtles are the garbage disposals of our waterways. They are important top-line omnivores, consuming largely plants and fish. They also eat carrion, amphibians, invertebrates and on rare occasions, snakes, mammals and young waterfowl. Their threat to waterfowl has been greatly exaggerated through myth, and in reality, only influences populations where turtle and young waterfowl density is high. Snapping turtles do not like to exert too much energy and prefer to lazily forage or hunt by surprise. They bury themselves in mud with their mouths open and strike suddenly as unsuspecting prey swim by. If forced to hunt, snappers stalk prey slowly and silently. They actually have the ability to fold back the skin on their necks and legs to reduce drag. Snappers have great vision and hearing, and as adults, have very few predators. Humans are the biggest threat to adult turtles. The number one killer of adult snapping turtles is automobiles.

Snapping turtles in the wild have a life span of about 30 years. They start their lives as an egg in the female after she emerges from hibernation. Upon waking, snapper males mate violently with females, inseminating the female and establishing dominance in a home territory. Come June, the female will venture out on a nesting migration. She will travel up to 3 miles - often on land and roads - in pursuit of the perfect nesting location (sunny and sandy), doing so at speeds of up to 1 mile per day. Once she finds her nesting spot (which is often close to a small stream or dam since young snappers are very poor swimmers), she will dig a nest chamber and lay between 22 and 62 ping pong ball-sized eggs. Babies will hatch in 90 to 120 days and head straight to water using homing abilities. Individuals will travel to their hibernation sites by October, choosing water bodies with adequate dissolved or atmospheric oxygen.

Snapping turtles in the wild have a life span of about 30 years. They start their lives as an egg in the female after she emerges from hibernation. Upon waking, snapper males mate violently with females, inseminating the female and establishing dominance in a home territory. Come June, the female will venture out on a nesting migration. She will travel up to 3 miles - often on land and roads - in pursuit of the perfect nesting location (sunny and sandy), doing so at speeds of up to 1 mile per day. Once she finds her nesting spot (which is often close to a small stream or dam since young snappers are very poor swimmers), she will dig a nest chamber and lay between 22 and 62 ping pong ball-sized eggs. Babies will hatch in 90 to 120 days and head straight to water using homing abilities. Individuals will travel to their hibernation sites by October, choosing water bodies with adequate dissolved or atmospheric oxygen.

Turtle hibernation (sometimes referred to as brumation in reptiles), is a fascinating process. Ideal hibernation sites are limited and snappers will often aggregate in favorite areas, sometimes on top of one another, to get through a winter. They will locate a spot just below the frozen surface where they will bury themselves in mud or lay atop it. They lower their body temperatures to just above freezing (34 degrees F) and slow their heartbeat to 1 beat every couple minutes. Turtles in Wisconsin will not breathe through their lungs from October to early May. They instead take in oxygen from the water through specialized cells in their throats and tails in a process called extrapulmonary respiration. Hibernation is energetically expensive and old and young turtles will sometimes expire before emerging again in the spring.

Fun Facts

You thought dinosaurs were old?! Snapping turtles, as we know them today, date back some 40 million years in fossil record. However, the most primitive turtle, Odontochelys (shown at right), is even older, dating back some 220 million years! For comparison, dinos are only about 150 million years old.

You thought dinosaurs were old?! Snapping turtles, as we know them today, date back some 40 million years in fossil record. However, the most primitive turtle, Odontochelys (shown at right), is even older, dating back some 220 million years! For comparison, dinos are only about 150 million years old.

Help a guy out! Occasionally snapping turtles have to be moved from danger. The safest way to do so is by picking the turtle up by the back edge of its carapace, not by its tail. Picking up a small snapper by its tail may not harm it, but doing so with an adult can dislocate their spine and/or cause severe damage.

Curiosity killed the turtle?? Snappers are very curious by nature, which sometimes leads to their demise. Snappers will often swim right up to boats and humans, investigating them with a gentle touch of their nose. And while it makes for great drama, snappers do not hunt in waters deeper than a person can stand in and do not attack swimming humans.

Boy or girl? Now you can choose! Snapping turtles have temperature dependent sex determination (TDS). The sex of the turtle is actually determined by the temperature at which the egg was incubated. An even ratio of male to female means the eggs were incubated at a perfect 82 degrees F.

*Resources used to write this article include: Wisconsin's Department of Natural Resources "Turtles and Lizards of Wisconsin", Stan Tekiela's "Reptiles and Amphibians of Wisconsin" and the websites www.tortoisetrust.org, www.biokids.umich.edu, www.scienceblogs.com and www.wikipedia.org

*Photo credits: Snapper and baby by Robert Hay, snapper carapace and plastron illustration on tortoisetrust.org, snapper youth by Bruce Halmo, hibernating turtle under ice by Ellen Hawley and Odontochelys on scienceblogs.com