I’d barely noticed the lampposts in the daylight, but suddenly I couldn’t stop thinking about how familiar they looked—in fact, I had to fight the urge to point them out to my fellow community scientists.

Then it hit me: I’d become so invested in our search for monarch butterfly eggs that now, they were appearing to me at every turn. At the top of each lamp at Washington Park, a lightbulb sits inside of a vertical glass half-oval, which is flattened at the top and decorated with longitudinal grooves. That chicken-egg shape and those uniform stripes were exactly what I’d been telling volunteers to look for during our monarch larva surveys, and now here they were, magnified millions of times and glowing, as always, but this time with electric light instead of a life force.

A monarch butterfly egg found on a milkweed leaf. The eggs are about the size of the tip of a ballpoint pen. credit: Keith Roragen

Every week at each of our three branches during June, July and August, members of our Research and Community Science Department team up with UEC Outdoor Leaders and volunteers to take part in the Monarch Joint Venture’s Monarch Larva Monitoring Project (MLMP). The project was established in 1997 by University of Minnesota researchers who understood the power of utilizing community scientists—individuals who contribute to a scientific field in which they don’t have formal training—to monitor monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) population and migration trends throughout North America and New Zealand. Data gathered through the MLMP, which these days is also affiliated with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum, have vastly improved entomologists’ understanding of these insects’ ecology and migratory patterns, threats to their survival, and effective conservation methods.

Although one of my greatest joys during my summer internship with the Urban Ecology Center has been educating community scientists about monarchs’ crucial ecological role as pollinators, I was thrilled to miss one survey recently to chat with Dane Elmquist, a former assistant program coordinator for the Monarch Lab at the University of Minnesota. The other day I was thrilled to chat with Dane Elmquist, a former assistant program coordinator for the Monarch Lab at the University of Minnesota.

During his time at the lab, Dane contributed to a 2017 paper that utilized data made available by MLMP volunteers like the ones who join us at the Urban Ecology Center. Titled “Tachinid Fly (Diptera: Tachinidae) Parasitoids of Danaus plexippus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)” and published in the journal Annals of the Entomological Society of America, the paper documents community scientists’ discoveries of parasitic tachinid flies that use monarch larvae as hosts. Tachinid flies, which are native to North America and belong to a family called Tachinidae, lay their eggs—up to a dozen at a time—on monarch larvae and other caterpillars. Once hatched, the fly larvae burrow into their host caterpillar’s body and emerge from a dead or dying caterpillar or chrysalis, depending on the fly species, once they’re ready to form a pupa themselves.

A monarch caterpillar parasitized by tachinid fly eggs. credit: David Illig

The idea for the paper hatched from a dilemma that many Urban Ecology Center members—those food-scrap-composting, subsistence-gardening, specimen-gathering types—may find familiar: not enough freezer space. During a freezer deep-clean at the Monarch Lab, researchers recognized the breadth of the archive of preserved tachinid specimens they’d been storing since the launch of the MLMP. The emerging and newly emerged larvae had been collected and mailed to the Monarch Lab from across the continent, by community scientists who’d been rearing the host caterpillars in their homes. “We just said, ‘Let’s see what we can do with all this data,’” Dane told me.

What they could do was enlist Dr. John Stireman, a professor in the Biological Sciences Department at Wright State University, who Dane described as “the United States’ tachinid fly guy.” Dr. Stireman made the species identification component of the paper possible, Dane told me because identifying Tachinidae species requires so much expertise that it often comes down to the length of a thorax hair.

Hairs and all, seven species of Tachinidae are identified in the paper, including one species that had never been described before, dubbed Leschenaultia. Dane, Dr. Stireman, and the rest of their team also identified Tachinidae as the primary parasitoid (that is, a parasite whose larvae eventually emerge from their host) for monarchs, and confirmed that tachinid fly larvae are typically fatal for their host caterpillar. The researchers determined that 9.8% of all monarch larvae become host to a tachinid fly larva, and they observed the first documented case of multiparasitism, or more than one parasitoid species emerging from a host, in this family.

The paper lays the groundwork for a variety of future research questions. There’s the newly described species, and there’s also much more to be learned about Tachinidae multiparasitism, as well as speculation that some species in this family may have evolved to specialize in parasitizing monarchs. Future entomologists will have not only the shoulders of Dane and his team to stand on, but also a quarter century’s worth of data contributed to the MLMP by community scientists.

Dane recognized that some skepticism surrounds the validity of data collected by folks without formal scientific training, but he praised the MLMP’s rigorous protocol and easy-to-follow instructions. It’s also crucial to recognize that some skeptics forget the many barriers to obtaining that training, or would simply prefer that scientific understanding remains in the minds of those who were able to obtain it.

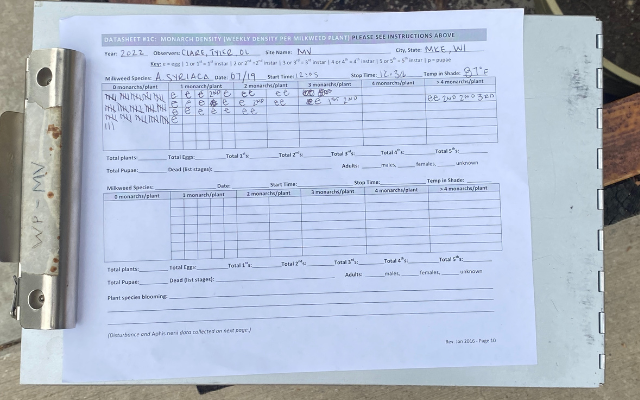

An example of a data sheet from a recent (and very fruitful) survey.

An example of a data sheet from a recent (and very fruitful) survey.

“The paper would not have been possible without this level of data, and this level of data would not have been possible without [community scientists],” Dane told me. Regardless of their passion and dedication, Monarch Lab employees alone couldn’t have amassed data on more than 20,000 individual monarchs: only a network of volunteers and hobbyists, committing their free time to understanding the world around them and advancing scientific understanding for present and future generations, could have built a database as powerful as the MLMP’s.

These days, Dane is a PhD candidate in entomology at the University of Idaho and a Research Fellow for the United States Department of Agriculture. You can hear about his parasitoid research in his own words here.

Since the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s July 21 announcement that it now considers monarch butterflies endangered, I’ve been even more eager for each MLMP survey and for the opportunity to share these creatures with new community scientists. I’m already chronically checking the leaves of every milkweed plant I spot, even when I’m off-duty: if giant apparitions of eggs are the next manifestation of my devotion to Milwaukee’s monarch population, then I’ll gladly keep looking up.

Written by Clare Eigenbrode, our Science Communication Summer intern, 2022!