Lanius excubitor. The Northern Shrike's Latin name means "sentinel" or "watchman butcher" and her hunting behavior was initially described as wanton killing. But scientists were wrong. She is no ruthless killer. The Northern Shrike kills out of need and in foresight.

The Northern Shrike can be found in the summer throughout Alaska and Canada and wintering from southern Canada and into the Northern United States. In Wisconsin, it can be found in open areas consisting of shrubby trees and tall perches, and often prefers forest and wetland edges.

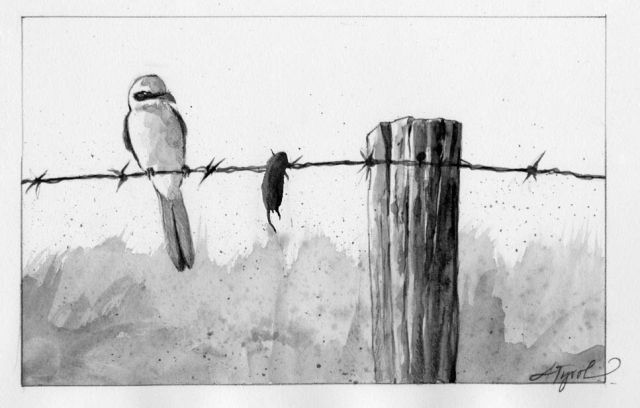

The Northern Shrike is a gray colored passerine with a thin black mask and thick hooked bill. It feeds primarily on small mammals, birds, and invertebrates but is best known for its unique feeding behavior. The "sentinel butcher" catches more prey then it is able to eat and spears the leftovers on thorns, barbed wire or sharp twigs. It will come back to these spots when food supplies are low. Shrikes will hunt mammals as large as an ermine, using its bill to carry back large prey and tear it apart.

The Northern Shrike is a gray colored passerine with a thin black mask and thick hooked bill. It feeds primarily on small mammals, birds, and invertebrates but is best known for its unique feeding behavior. The "sentinel butcher" catches more prey then it is able to eat and spears the leftovers on thorns, barbed wire or sharp twigs. It will come back to these spots when food supplies are low. Shrikes will hunt mammals as large as an ermine, using its bill to carry back large prey and tear it apart.

Both the male and female shrike sing throughout the year while the male will sing readily in the winter and into early spring. Their movement is determined by the population fluctuations of their prey, moving where rodents' populations are most abundant. They hunt from a perch, holding completely still until the moment they swoop down and pounce and sometimes also after hovering midair over its prey.

The Northern Shrike's nest can be found in trees fashioned into a deep, open cup of twigs and roots. It is intertwined with feathers and hair and lined with a compact mat of feathers, hair and grass. A typical clutch size is 4-9 eggs which are incubated for 15-16 days. Fledglings are able to fly at 20 days old.

Did You Know?

Riverside Park has its own Northern Shrike snowbirding in the Arboretum (at right)! It was first spotted 5 weeks ago in a tall tree close to the rock arch in the Arboretum and has been spotted almost daily since. This is only the second time a shrike has been spotted in any of our three parks and the first time one has hung around for more than a day. The restored habitat in the Rotary Centennial Arboretum is a perfect place for the shrike with its open savannah and interspersed tall trees.

Riverside Park has its own Northern Shrike snowbirding in the Arboretum (at right)! It was first spotted 5 weeks ago in a tall tree close to the rock arch in the Arboretum and has been spotted almost daily since. This is only the second time a shrike has been spotted in any of our three parks and the first time one has hung around for more than a day. The restored habitat in the Rotary Centennial Arboretum is a perfect place for the shrike with its open savannah and interspersed tall trees.

A shrike sighting in this area is cool enough that local bird enthusiasts have been trekking to Riverside Park to see the bird and add it to their county year-lists. There has even been a friendly plea to document the bird on December 20th – our Christmas Bird Count. The Christmas Bird Count is a nationwide event where birders follow specific routes to spot as many birds as possible on a given date. Counties tally up the total number of species and often create friendly rivalries to see who can spot the most birds. Madison has beat Milwaukee year after year in species totals, but a few local birders are driving a charge to put Milwaukee on the top this year. The Riverside Park Northern Shrike is the only one of its species being reported in Milwaukee right now and a documentation of this bird could be the species that makes Milwaukee the 2015 champion! Join us on December 20th to partake in the challenge and see if Milwaukee can reign as the Wisconsin birding title!

Fun Facts

Fun Facts

- So if a group of crows is called a murder and a group of geese is a gaggle... what do you call a group of shrikes? Why, a "watch" of course!

- Who needs talons when you've got a beak like this? Northern Shrikes actually lack talons which is why they often catch and kill birds using their beak instead of their feet.

- And for my next magic trick... A shrike's nest is built so deep that when the female incubates her eggs, all that can be seen of the bird is her tail tip.

- One decade and 2 years ago... the world's oldest Northern Shrike was born. The oldest wild shrike lived to be a little over twelve years old, but they more often live to be about 4 years old.

*Photo Credits by (from top to bottom): Garth McElroy, Larry Master, Urban Ecology Center volunteer Bruce Halmo, and illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.

*References used in this article include: David Allen Sibley's Field Guide to Birds of Eastern North America, the phone app iBird Pro, and the websites audubon.org, allaboutbirds.org, wikipedia.org and northernwoodlands.org